THE BOOK

by Jack Kendle

******************************

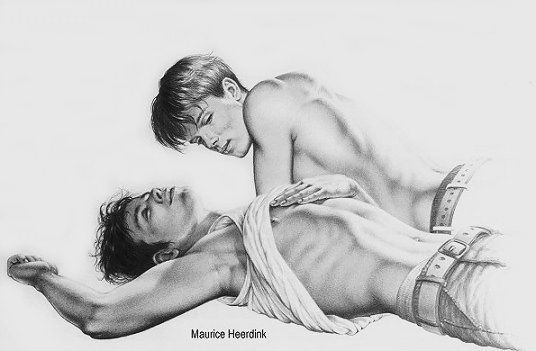

I am grateful to the distinguished artist, Maurice Heerdink, for his permission to reproduce three of his excellent pictures, without which this story would be the poorer.

Other images are, to the best of the author’s knowledge, in the Public Domain. If, however, you feel that an image reproduced in this story is in breach of copyright and can be proven to be so, the image in question will be removed.

©2011 Jack Kendle – All Rights Reserved

******************************

TO THE READER

Although most of the places and locations described here are real, this does not mean that the persons represented here or the actions described in this story actually took place at these real locations, nor should it be inferred. The locations are used purely for atmosphere and veracity. The story is of course fiction from beginning to end and similarly, all characters are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

The story contains scenes of man/boy sexual relations, some of which are non-consensual, which may upset some readers and this being the case, they are advised not to read any further. Similarly, if the reading or downloading of such material contravenes laws or regulations in your community, state or country, then you do so at your own risk.

******************************

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

The Present

Peter Taylor, 23 – Book illustrator and main protagonist

Jeremy, his current lover – Lawyer (takes no direct part in the action)

Sebastian Walker mid 30’s – Portrait photographer, a neighbour

Dr Jerzy Szczepkowski – Peter’s downstairs neighbour (takes no part in the action)

Albert Pennyweather, 70+ – A regular at “The Crown” – Peter’s local pub

Simon Stafford-Jones 50+ – Retired professional singer

Lars, 16 – Peter’s young friend and eventually, his lover

Stanhope Robertson 80+ – Retired organist & choirmaster

Lancelot Cruickshank – Deceased. Former Rector at St Giles Church

DCI Morrison – Police detective, London

DS Richards – his sergeant (London)

DS Barnes – Police detective, Bournemouth

Sergeant Villiers – Policeman (Bournemouth)

Joshua Hallam – Peter’s agent

Hugo Montagu – 14th Earl of Pevensey

Phyllida, Lady Pevensey – his wife

Kieran Montagu, 13 – their son

Ambrose – butler to the Pevensey household

Dr. Towns – Archeologist

Douglas Champneys – current Rector of St. Giles

The Past

Man in bookshop

Izaak Waldon, author

Tom Thatcher, about 12 y.o. (takes no direct part in the action)

Philip J.W. Montagu, 3rd Earl of Pevensey

John Montagu, 2nd Earl, Philip’s father

James Venables, 14 y.o. Apprentice, son of

Edward Venables, 46, Master mason

Will Fremantle, 13, chorister at St. Giles, diarist.

******************************

“Use him as thoughe you Loved him, that is, harme him as little as you maye poffibly, that he maye live the longer”

Izaak Walton, on the use of frogs as bait – from The Compleat Angler

******************************

The book is gone now and I know I will never see it again. Even now, as I sit at my desk, I vividly remember the texture and feel and slightly musty smell of the worn calfskin binding with its patina of age from much handling. I will never forget the shock when I first read that title page and the subsequent stories the book showed me.

How I came across this book and what it led me to might sound unbelieveable, but I assure you it all happened, exactly as I write it down. Everything.

But I must start at the beginning.

ONE

(SUNDAY – MORNING)

It was raining. Not just ordinary common-or-garden rain, but London Rain; the type of rain which, like stair-rods, clatters indiscriminately down from leaden skies on to grey slate roofs, squealing black taxis and the fume-belching red double-decker buses. Rain which, with the capital’s typical lack of subtlety and a mixture of Cockney brashness and the arrogance of a capital city, insinuates itself between tiles, down drainpipes, down the soot-caked walls of buildings some of which, for centuries, have survived innumerable such assaults, fills the gutters, overflows the cast-iron grilles, bearing on its inexorable tide the flotsam of the busy thoroughfare; discarded bus-tickets, burger wrappings, cigarette stubs and the yellow-brown leaves from the now nearly-bare branches of the plane trees lining both sides of the busy road. The noise of the downpour almost drowning out the hooting of the stressed-out drivers, weaving through the fleeing pedestrians, who, umbrellas up, dodge and scurry through the slow-moving traffic like carapaced, two-legged beetles of every shade and hue, seeking shelter from heaven’s watery invasion.

It was an early Sunday in November and I was in the Charing-Cross Road, on my way home from Jeremy’s. I had spent the night with him, saying goodbye – he was off to the States on a job for the next three months at least. I wouldn’t be going with him, not only because the high-profile case he would be working on would certainly take up eighteen hours of his day, but also because I just happened to have a project of my own which I was working on and which was due to be completed within the next month or so.

Perhaps I should introduce myself before I go any further. My name is Peter James Taylor. I am a twenty-three-year-old gay man and I am what people call – not quite accurately – one of the idle rich. Idle because I don’t have a fixed nine-to-five job, but work as an illustrator, mostly those coffee-table type of book, authors’ personal views on a place, be it city, town, location or country. Rich, because I am good at my job and can now name my price for the jobs I do and thus in the enviable position of being able to choose my projects. My fortune is due also to the untimely death of my parents, who themselves were certainly not idle and very, very rich.

On my way home the heavens opened, catching me without an umbrella. I ducked into the nearest doorway. It was a bookshop – hardly surprising really, as Charing-Cross Road is lined with bookshops for much of its length.

As I dashed inside, I was vaguely aware of green paint, plate-glass with gold lettering and the tinkle of the small bell as I pushed the door closed behind me, blocking out the pelting rain and the noise of the traffic, hissing over the slick tarmac.

Not only was it suddenly very quiet here in the shop, the gloom was positively Stygian and my eyes took a while to accustom themselves to the dimness within. I was aware of long lines of shelving, sagging under the weight of hundreds, thousands of books, stretching away into the dim interior of the shop. Tables piled high with books reduced the floor space to narrow corridors, towers of books threatening to topple over and engulf me in fluttering avalanches of paper, print, leather and pasteboard.

There wasn’t a soul in sight. I peered past the vertiginous towers of books, hearing nothing but the ticking of what sounded like a large clock, as yet still hidden from view. As my eyes began to get used to the dimness, I began to get my bearings and started to walk down one of the aisles before me. I heard the still hidden clock begin a sonorous chiming. I glanced at my watch; noon. I remember vaguely wondering where there was wall-space for a clock; every available surface seemed to be covered with shelving or tables piled high with books. There was a faintly musty odour; not at all unpleasant, reminding me slightly of the bark of trees or leaves in a foggy night. Now and again, there was a faint rustle; I fancied it might be mice, scurrying to and fro behind the vast brown bookcases. What a feast they had! I wondered whether the proprietor, whoever and wherever he was, consigned the lesser books to the lowest shelves, where the mice (and possibly rats as well), could gnaw and nibble without destroying great works of Literary Art.

“Hello! Anybody there?” My voice sounded faint and as there was no echo, it fell flatly to the ground, I fancied, unheard.

My eyes glanced along the uneven rows of books, picking out various titles on the spines. Some were great tomes, inches thick, with ornate lettering, stamped in gold, others slim volumes with no word to indicate what lay between the covers. I seemed to smell centuries of dust, imagining it, inches thick, lying over everything in this seemingly forgotten world. My fanciful imagination felt as if this place had been abandoned for millennia; it had the air of forlorn, yet dignified solitude, like a Miss Haversham Wedding Breakfast of books for the mice and beetles.

I slowly ventured deeper into the sepulchral interior. Ceiling-high shelves met at rightangles, narrow avenues of books leading in all directions. The place was huge! Much larger than one would have thought, passing by. As I went deeper into the almost palpable gloom, all noise from the outside faded to nothing and the silence, like the towers about me, became almost oppressive. Faintly, I still heard the ponderous chimes of the clock, somewhere far away, it seemed to me. Still no sight nor sound of an owner or employee. Only the tiny rustlings and an occasional creak from the overloaded shelves.

The shop seemed enormous. I could see no sign of walls at the ends of the narrow lanes of books, only vague shadows of more shelves and yet more books. Looking down, I saw thick dust on the bare floorboards. I glanced back and saw that only one set of prints followed me; mine. I felt a slight shiver run down my spine. This was distinctly odd. Had no-one honestly been into this part of the shop in all the time it took for that amount of dust to form?

I looked at the shelves; more dust, books seemingly untouched for years, decades even. This was very strange. More than strange, it was positively creepy.

I was just about to turn and retrace my steps, when I was literally halted in my tracks by a sound. In normal circumstances, the sound would not have awakened any suspicion or fear on my part, but here, now…

It was a small sob, a child’s sob. It didn’t come from behind me, but somewhere ahead of me, as far as I could tell. Somewhere ahead in the gloom. I looked down again; still no footprints ahead of mine. Yet the sob, though stifled, I fancied, was distinct. I was sure I heard it, or was I?

I stood stock still, trying very hard not to breathe, straining my ears for every sound, my eyes wide open and scanning my surroundings for any movement. The place was as still and as quiet as the tomb, which is why that alien sound had startled me so. There it was again! So soft, yet it wasn’t my imagination. It was a sob, made by a child, as far as I could make out and it definitely came from ahead of me in the darkness.

I inched forward, every nerve jangling, a sweat beginning to break out on my body, droplets coursing down my back. As I slowly moved forward, I was aware of the sound of quiet sniffling, like a child’s crying. It was so soft, I thought I must have imagined it, but there it was again, still very quiet, but I had the feeling it was closer. I reached an intersection in the tall shelves, a kind of crossroads. Which way? Where were these sounds, if indeed they were real and not the product of my imagination, coming from?

At the junction, I stopped again, and as I looked down the three aisles, I listened out for the sounds to come again and if they did, see whether I could work out from whence. There! I heard it again! A gentle sob followed by a sigh. A sigh so heartbreakingly sad, a tremulous sigh as if from one in deep grief. It came from my left, and as far as I was able to judge in this strange, dead acoustic, only a matter of feet away from where I was standing. Who was making these forlorn sounds? And how did they get there? It really sounded like a child’s voice, and I wondered what a child was doing here, all alone, in this place.

I turned left and walked as quietly as I could, ears and eyes alert for any sight or sound of my invisible companion. I arrived at an intersection and, out of the corner of my eye, thought I saw a figure, only feet away, in the gloom, standing by one of the shelves, looking upwards. But as soon as my mind registered it, it was gone. It must have been a fraction of a second, maybe a fraction of a fraction, but I had the distinct impression that I had seen something … no … I had seen someone.

I went quickly to where I imagined it to have been. Nothing. I looked along the endless corridors of shelves, disappearing into the gloom. Only my footprints in the dust. I looked down at my feet and stared in horror at what I saw: the small imprint of a child’s foot; heel, arch, five toes. A child’s bare foot. Just one. I fell back into the shelves, fingers clawing at the leather, hand-tooled spines, almost pulling them from the books, dust flying into the air. I felt as if my knees had turned to jelly. I must be imagining things, the poor lighting playing tricks on me. I looked down again. The child’s footprint still there and next to it, the mark as if a drop of water had landed in the dust – a teardrop.

I lay back against the bookshelf for support, my hands instinctively holding on to the books in the shelves to prevent me sinking to the ground. My breathing was laboured, as if I had been running and there was sweat on my brow. I found I was trembling as if in fear. I had to be imagining this, some sort of dream. I would wake up soon, I was sure – or rather I hoped I would.

I looked around me. My eye caught sight of the corner of a book poking out over the edge of the top shelf on the bookcase opposite me. My nanosecond’s vision returned; hadn’t whoever I imagined I saw, been looking up towards that spot? Slowly, I reached up and my fingertips found the corner of the book. I teased it towards me until gravity took over and the volume dropped over the edge of the shelf. Somehow I managed to catch it, a small volume making a muffled slap as it met my outstretched palms.

As if a switch had been thrown, the place became brighter and the noise of the traffic outside was suddenly audible once more. I found I was right at the back of the shop – no long corridors of shelving stretching away into the distance, no sepulchral silence nor dust of ages. Looking down, I saw the plain brown floorboards of the shop, polished by years of browsers – no sign of a child’s footprint, nor teardrop. What had happened? Had I had some sort of blackout? Had I somehow or other had a dizzy spell, or even fainted? I had no recollection of falling to the floor, no feeling of dizziness. I couldn’t understand what had happened. I wasn’t drunk, of that I was sure. I had only had one drink with Jeremy.

The clock was chiming. Wait a minute! The clock was still chiming! I looked at my watch; noon. No time had passed! Yet, in that ‘no time’, I had walked along many yards of shelving, deep into the inner recesses of the shop, or somewhere, heard the sobbing of a small child, seen the book and taken it down from the bookshelf yet the clock was still chiming! This wasn’t just creepy, this was impossible! Yet there it was, in my hands, a small, leatherbound volume, obviously worn with age, with faint gold lettering; “The Compleat Angler”.

I was shaken out of my reverie by a soft voice at my elbow. Startled, I looked around to see who was speaking.

“Ah! I see the book has returned and found its new owner!” I looked at the man, for it was indeed a man, aged about seventy or so, I guessed, soft-spoken, snow-white hair wildly spreading in all directions around a pink tonsure, like a mad monk, I thought to myself. He must have noticed – who wouldn’t? – the stare of blank incredulity I gave him. His gaze indicated the small volume in my hands.

“It vanishes for years at a time, then suddenly out of nowhere, Pouf! it reappears in the hands of its next owner, or should I say caretaker.” He paused for a moment, screwing up his eyes as if trying to remember something.

“Let me see, it must be ten – no twelve years ago since it was last here. I remember the last one it chose…” he gave me a speculative look.

“I wonder… how long you’ll have it for? And why has it come back now? Hmmm.”

“But I didn’t choose this,” I said. “I didn’t come in here to buy a book. I came in to shelter from the rain…”

“The important thing is, you came in,” said the old man, enigmatically, his pale blue eyes twinkling behind his old-fashioned half-moon glasses.

“You might not have chosen the book, but it chose you! Take it, young man! I have no idea what’s in it this time, but may it be of use to you…” he paused, almost melodramatically, adding in a stage whisper, glancing about him as he did so: “…but use it wisely. Do no harm.”

Again he paused me and fixed me with his steady gaze, emphasising every word with a finger pointing at me. “Do no harm!”

“What am I supposed to do with Walton’s The Compleat Angler?” I asked, somewhat amused by the old man’s theatricality, “I don’t even fish!”

“Take it home and read it carefully. Use it wisely!” the man repeated, beginning to move away.

“But, but what does it cost? I’m not buying something for which I have no use!”

“You will find a use for it, young man!” he replied. “Take it! No charge! Free. Gratis! Now go! Look, the rain has stopped. Shoo! Go!”

The old man more or less pushed me out of the shop. He was right. The rain had stopped. I looked down at the book, lying innocently in my hand. What a very weird thing indeed! Firstly, what had happened in there? Had I blacked out? Was I dreaming all this? A speeding cyclist rushed right past me, almost knocking me down. I almost went flying. The pain in my shin proved it: I wasn’t dreaming!

Had I slipped into a parallel universe? Had I witnessed a haunting? As my mind whirled, the explanations became more and more outlandish, bizarre and crazy. I had to face it, there was no rational explanation. Somehow or other, I had picked out a book, been given it by the proprietor and been given a bum’s-rush out of the shop.

I turned and went back in. The lights were blazing, several browsers were scattered around the shop, whose back wall I could now clearly see and a young shop-assistant at the till looked up and asked if she could be of assistance. The old man I had just spoken to was nowhere to be seen.

“Er… I wonder, could you tell me how much this costs?” I asked, holding out the small well-worn leather volume. The girl at the till gave me an odd look.

“No, sir, I’m sorry, but we don’t sell second-hand books here.” She made it sound as if I had just shown her hard-core porn. With even more undisguised distaste, she added, “We only sell new books.” She continued to look at me as if I might be slightly mad and about to cause trouble.

“Oh, er… thank you,” I replied somewhat awkwardly, putting the book away, rather hastily, as if it were an unclean thing.

I looked around me once more. This was quite a different establishment to the one I had just moments ago exited. I felt the eyes of the young girl at the counter on me as I left the shop, even more confused than before. Why had I been given this book, a book I had no use for and what was all that babble about it choosing me and the appearing and disappearing stuff? I reckoned the old bloke in there must be mad and I had just been the victim of a practical joke. Maybe I was being filmed secretly and any minute now someone would come leaping out at me, all fake tan, white teeth and exuding equally fake bonhomie, telling me I was on “Candid Camera” and would I look over there and smile?

I studied the little volume, lying innocently in my hand, turning over the recent events in my mind.

Fact number one: I had rushed into the shop out of the rain.

Two: I had heard or thought I heard the sounds of a child crying.

Three: I saw – or thought I saw a small figure, a boy, whom, I thought, was sobbing and seemed to be trying to draw my attention to the book which I now held before me.

Four: I was approached, one could say I was almost accosted by an elderly gentleman who insisted I take the book. What had the old man been rambling on about: Use it wisely, do no harm! He must be mental, I thought.

Five: did the man have any right to give me the book which must be merchandise? And yet… the shop I went back into seemed to be quite a different place!

Six: the sales assistant had told me quite categorically that the book was certainly not one of theirs – they only dealt in new books, she had said. Well, I had done my best to return the book, but no-one was interested. Convinced that at least I wouldn’t be chased down the street by someone accusing me of shoplifting, I pushed the book into the pocket of my Burberry and headed for home, my head reeling from the inexplicable experience I had just had.

As I walked, I gradually came to the conclusion that I must have had a sudden drop in sugar-levels, which to all intents and purposes made me almost faint and in that brief second, I must have had this strange hallucination.

But something niggled at the back of my mind. Something wasn’t quite right with that explanation. Just in case, however, I took a small chocolate bar I keep about me for just such an occurrence (I have a medical condition which means I have to keep a watch on my sugar levels) and as I allowed the dark, sweet chocolate to melt in my mouth, I began to calm down and rationalise.

‘It must have been a drop in my sugar’, I thought, as I neared home.

TWO

(SUNDAY – LUNCHTIME)

Home, was not far away, a leisurely five-minute walk brought me to my front door close to Seven Dials. My flat was the top floor of a flat-fronted, brick-faced Georgian house in one of the narrow streets just off the junction. Not ostentatious, it nevertheless had all that I needed for comfort. Both my parents were dead, victims of a car accident three years ago, when I had just turned twenty. They had left me more than adequately provided for; in fact, as their sole beneficiary, I had no need to work for a living. With some of my inheritance, I bought and furnished this flat in central London, invested most of the rest and lived off the interest.

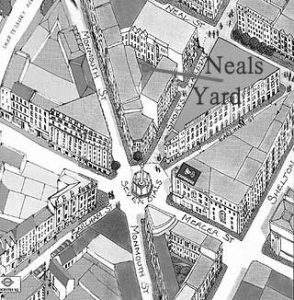

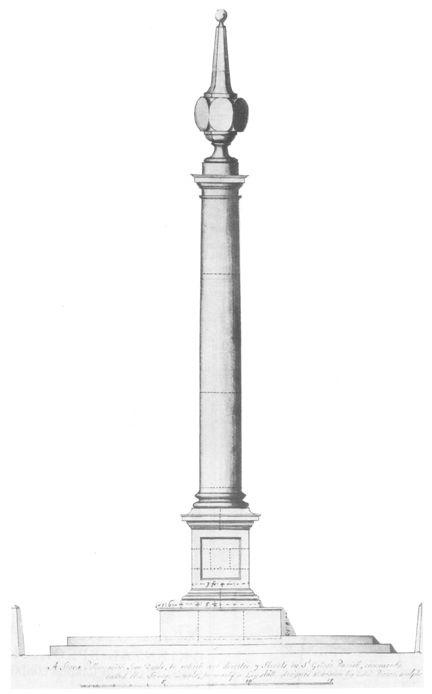

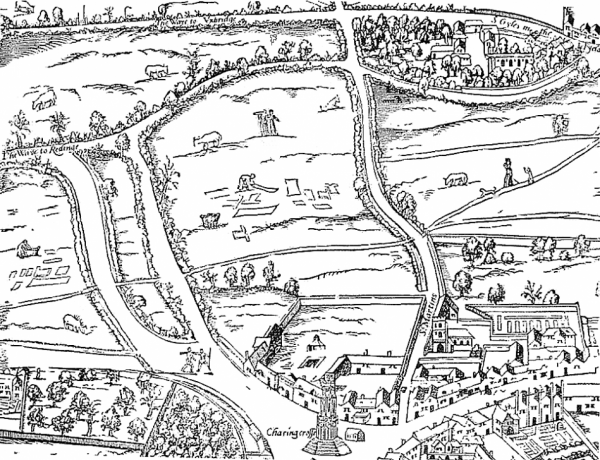

The original layout of the Seven Dials area was designed by Thomas Neale in the early 1690’s. The original plan had six roads converging, although this was later increased to seven. Following the successful development of the fashionable Covent Garden Piazza area nearby, Neale aimed for the Seven Dials site to be popular with well-off residents. This was not to be, however, and the area gradually deteriorated. In the centre of the open area still stands a tall column, with a sundial based on that which had stood there from earliest days. At one stage, each of the seven apexes facing the column housed a pub. Now only one remains, The Crown. The original sundial column was removed in 1773. It had been believed that this was due to being pulled down by an angry mob, although recent research suggests that it was deliberately removed by the Paving Commissioners in an attempt to rid the area of undesirables. In those times, according to contemporary accounts, the monument was a renowned meeting place for whores, both male and female and other disreputable characters. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, press-gangs roamed the streets, capturing young men and boys worse for drink from any of the pubs at Seven Dials and condemning them to a life in His Majesty’s Navy – or darker, more sinister fates.

I was the only full-time resident in the house. The basement had its own entrance around the side. It seemed to be the offices of some foreign import-export firm, according to the very tarnished brass plate on the door. “Offices” is probably too grand a term; more likely the basement flat was simply used for storage. The windows were grimy and the equally shabby curtains were always drawn.

I never saw any signs of life there and certainly no-one either entering or leaving the place. I did notice, though, that the parking-place which went with the flat was occasionally filled with a dirty and rather beat-up old windowless Ford Transit van. It would stay parked there, usually for no longer than a few days every month or so. That was all that showed that the flat was not derelict. However, whoever it was that rented the place must have kept up with their payments and I knew that the Residents’ Association payments were dealt with by a local solicitors’ firm.

A prime piece of real-estate in the heart of London standing empty and ostensibly unused. That mysterious import-export company obviously had money. Occasionally I idly wondered what kind of imports and exports, but other than that, I didn’t give the place a second thought.

The ground floor housed a portrait photographer’s studio and the middle floor was rented out to some sort of academic, who was very rarely home, spending most of his time, I assumed, on expeditions to all corners of the globe.

The photographer, Sebastian, was the only near neighbour I knew. He was about thirty or so. I occasionally met him in the hallway or in the local delicatessen. He did well and many of the portraits he displayed in the window of his studio were of the rich and famous.

The academic was an anthropologist, from somewhere in eastern Europe, I think – Poland I thought, who spent months at a time away, probably looking for lost tribes deep in the Amazonian jungle or cannibals in Papua. I had only seen him once or twice; he couldn’t have looked less like the “Indiana Jones” type – he was short, almost totally round and with thick spectacles. The only times I saw him he was dressed in a thick dark overcoat and large scarf which all but obscured his face. He reminded me of a very fat Mole from the “Wind in the Willows. There was no name on his doorbell, but Seb, who seemed to make it his business to know all there was to know about the local area and our neighbours, assured me that the man was from Poland and was called Jerzy. He couldn’t pronounce his surname, saying it lots of ‘s’s and z’s’.

As a consequence, the large Georgian house was deserted most weekends, although Sebastian might occasionally come in for a sitting and if the academic was at home, he stayed indoors, probably writing some learned thesis, or poring over maps, I fancifully thought.

I lived a quiet life. If I wasn’t staying at Jeremy’s, he was here with me and we might occasionally go to the cinema or the theatre, although most of our time was spent at home, either in bed or else just reading, nattering – or just cuddling.

I met Jeremy shortly after my parents’ death. Although still a young man, aged only thirty, he had become a partner in the small solicitors’ firm who oversaw my parents’ affairs and my first meeting with him was when he told me how wealthy I had just become.

We had a few meetings over the months following my parents’ death, to sort out the sale of the house and all the other stuff and one day, almost by accident, after a long meeting involving probate, taxes, investment-portfolios, I found myself asking him if he wanted to come and have a drink with me at the local pub. He gave me his charming lopsided smile, blue eyes twinkling, and said he thought I would never ask! The rest, as they say, is history.

We’ve been together now for nearly three years. We don’t live together; he keeps his bachelor pad in Islington for when he needs to do some serious solicitor work and I have my own space to myself. We enjoy this arrangement; flexible though not mutually exclusive. I think we both need our own time and space for ourselves. We are also not exclusive partners. At the outset, we both agreed to have a ‘no strings attached’ relationship: if Jeremy found a handsome guy (I know he has fantasies about black guys) that he wanted to have fun with, then fine. The same went for me – my tastes ran to younger guys, a ‘bit of rough’ – some of the workmen who occasionally drank at the pub on the corner were very good-looking young men and not averse to bit of gay sex on the side, as long as their mates didn’t suspect. The funny thing was, that these ‘mates’ were also having a bit of arse on the side! Despite our freer lifestyle, Jeremy and I had a happy and stable relationship. Ours went deeper than just a ‘quick bit on the side’ – we might spend days together without making love, we didn’t feel it was such a big thing; so our ‘sexcapades’ kept our libidos in check.

I arrived home via the local delicatessen to stock up on my favourite Kenya Blue Mountain, a few slices of Parma ham, some home-made ‘tapinade’ and a couple of freshly-baked rolls as well as the proprietor’s own pistachio-flavoured ice-cream; lunch was usually a simple affair when I was at home alone. Adding a couple of bottles of Montepulciano, I paid and walked the last few yards home, stopping off to buy a newspaper from the newsagent’s on the corner. I skirted around a fenced-off area, which boded ill, I thought. With a mental sigh, I envisaged being disturbed by the rattle of pneumatic drills over the next days or even weeks. If there wasn’t building work going on in the neighbourhood, they were digging up the road.

Sebastian was coming out through the front door.

“Hiya Jack!” he said, giving me a flamboyant peck on each cheek. We had been an item for a short while, just after I moved in and before I got to know Jeremy. Seb is a sweet guy, but just a little too demonstrative and more than a little camp in manner for my taste . However, when Jer showed up, he was most gracious in defeat and he even treated us to dinner, to congratulate us. He still teases me and asks “how that boy-stealer” is.

“Hi, Seb. Jer’s fine,” I replied with a laugh.

“Well let me know when he dumps you. You can come cry on aunty Seb’s shoulder!” he replied with a flick of his immaculately cut and blow-dried wispy blond hair.

The joke was so old, he said it every time we met. “I will Seb, promise!” I gave my usual reply as I entered the house.

“I’m off for a week to my island paradise!” Sebastian called after me. “I’ve left a note for the milkman. You’ll keep an eye on the place and water the plants? Key’s in the usual place.”

He swept into his waiting cab in a waft of cologne, his long scarf billowing behind him.

Sebastian’s ‘island paradise’ was Mykonos, where he went two or three times a year. I knew he had a young man there, a fact I discovered after we had spent a night together and Seb had drunk rather too much and in his remorse had confessed to me all about his “Adonis on Mykonos”.

He had shown me a photograph of a young man in the briefest of Speedo swimming trunks; “Adonis” was the right name for the gorgeous hunk in the picture: piercing black eyes, curly black hair, worn shoulder length and a body to die for. He was a local fisherman and Seb had met him on one of his holidays and fallen head over heels in love with the young man, who must be about nineteen now. Lucky boy! Seb had bought him his own flat and, I suspected, kept him in the manner to which the youth wanted to become accustomed.

I had my doubts that such a relationship could work; “Adonis” had to be having a bit on the side, I thought – no young man could go without sex except for the sporadic occasions that Seb visitied the island. Whether or not he did was not my concern; it seemed he was very discreet and Seb was always excited to see him and always in a blue funk after his trips to Mykonos.

“Have fun!” I waved goodbye to Sebastian and walked up the stairs to my flat.

The Polish man was away as usual, but I did not have the same arrangement with him as I did with Seb. Someone came regularly when he was away, but I never saw who it was who took his mail or looked after the flat on the second floor. I occasionally heard the sound of his door opening and closing, or occasionally the vacuum-cleaner, but that was all.

Reaching the door to my flat, I fished in my pocket for my keys and my hand brushed past the little book I had been given earlier under such mysterious circumstances. The small volume slipped out of my pocket and landed on the carpet with a gentle thud, raising a small puff of dust. As it fell, I fancied I heard a small, quiet sigh. Bending down, I retrieved the leather object. It felt cold to the touch. Pushing open the door, I went inside, kicking it closed behind me.

My light lunch eaten and a glass of red wine in my hand, I went to the sofa with the small book and settled down to study the curious and mysterious tome. I opened the front cover, the slightly musty smell and dust making me sneeze. I was face to face with a picture of a gentleman in old-fashioned clothes, gazing at me out of the yellowing pages. I spent a few moments taking in the image; the man was kindly-looking, bearded, square black cap, lace ruff, puffed sleeves and a black gown over what seemed to be a surplice. In the background was a cityscape, I assumed it was London, although I couldn’t say for sure. The man’s oddly gnarled hand was holding a book not dissimilar to that which I now held – perhaps he suffered from arthritis? I particularly noticed his eyes, large and kindly, his brow slightly furrowed. He looked gently and I thought, a little sorrowfully out at me.

Deo Gratias

I turned the page, totally unprepared for what stood there.

The

Compleat angler

A JOURNAL

here compiled

by

izaak walDoN Esqre

wherein are descrybed

the sad tales of the baityngE, pErsuit and capture of

boyEs & youthes

for sportE & perverse pleasure – also a description of those places where they have many beene secretlie DIsPOzED

printed at the sign of the crown

IN MERCER’s lane, london

MDXCIII

I had to read and then re-read the title-page to be sure that I hadn’t misread or misunderstood the shocking message contained therein. Still scarcely able to believe what I had just read, I turned back a page and took another, longer look at the picture of whom I assumed was the author. He looked more like a clergyman than a pederast, but, I thought wryly, that was nothing new, in the light of recent exposés of clergymen and their abuse of children. Nothing new under the sun, then! I worked out the date from the Roman numerals at the bottom of the page; 1593.

What was Izaak Walton, the famous author doing writing not one but two books called “The Compleat Angler”? It was only then that I noticed the name of the author on the title page in front of me. It wasn’t Walton but Waldon. Close enough to be confused with the famous author of the treatise and anecdotes on fly-fishing. I went over to my laptop and Googled Izaak Walton. The date on the book, I now saw, was wrong; Izaak Walton lived from 1593-1683 – this was dated the year he was born! I found nothing under the name Izaak Waldon.

Images from the bookshop flashed through my mind; the sobbing boy, the vast, deserted bookshop, more like a mausoleum than anything else and then the odd man with his wild white hair and strange remarks about the book choosing me and use it wisely. I felt an involuntary shudder tingle up and down my spine, giving me goosepimples. This was decidedly creepy!

I turned the page, not knowing what to expect. What I saw produced all the effects I thought only happened in horror novels: the hairs on the back of my neck stood on end, I felt shivers running up and down my spine, I broke into a sweat, my hands shaking and clammy and I dropped the book. This had to be some sort of practical joke; a weird practical joke. But who would have thought of it, who could have put it into operation? Not for the first time that day, my mind reeled. I felt giddy and slightly nauseous.

I lay back into the soft cushions of the sofa and closed my eyes, trying to get my head round what I had just seen. How was this possible? My eyes returned to the small volume, lying almost innocently on the carpet by my feet where I had dropped it. It looked so innocuous, so ordinary where it lay, the warm brown of the well-worn leather almost gleaming in the late afternoon light. To the casual observer, it might conjure up images of a prayer-book belonging to a well-to-do country parson, such as in the picture I had just studied; or the diary of a noblewoman. Perhaps even a book of poems, a love-token from a young man to his beloved. Yet to me, it suddenly had become none of these; it had no innocent prayers, no gentle thoughts, no lovesick sonnets. The title page had been enough, but what I had seen on the following page gave the book a sinister, evil aspect.

The small boy sobbing flashed before my eyes again; now I thought I could guess why the poor mite had been in such distress. Yet… I had to open the book again, read what was contained within its pages. I felt an inexplicable compunction to see what was contained there. It was as if I heard thousands of tiny voices, childrens’ voices, crying out to me to read on and by so doing, save their souls, for I knew, with a certainty which was absolute, that it was too late to save their young lives.

My shaking hand reached once again for the book. I turned again to the page which had shocked me so deeply just before. I shall never forget those opening words:

By what manner and fortune hath thine hand and eye been drawn unto me, most honourable Gentleman Mr Peter Taylor Esqre of the Seven Dyles! For unto thee hath I turnéd and into thine hands hath the Spirit of thefe times – may they for ever be plagued – for this will be for thee and thine allies fuch a puzzlement until thine eyes shall be open’d and thou shalt feeke and, mercifulle God-wyllinge, discovere the Truth of these Thinges which have come to passe and save those who suffer yet.

By thine Hand, Master Taylor, may Deliv’rance be found and through it mighte come unto oure Soules the Peace for which we have struggled to fynde to no avail. Deepe are our Troubles and Tribulationes!

We beg Thee that thou mighte overcome the Darknesse which shroudes our soules and bring us Peace.

De Profundis clamavi ad Te

If this was a practical joke, a forgery, then it was a damn good one. For whatever reason, someone had gone to a great deal of trouble – but for what?

And why?

After hesitating, hardly wanting to touch it again, I nevertheless leant down and picked up the book and began to study it more closely. Everything about it seemed to be genuine; it looked right, felt right, dammit it even smelled right! There could be no doubt about it that the volume I held was from the late 16th Century and that the pages it contained were original.

So how did my name get there? Had there been some incredible coincidence and the book was addressed to my exact namesake from more than three hundred years ago? I had to dismiss that fact. But what was left was even more fantastic, even more unbelievable; someone in the late seventeenth century had written and printed a book that they knew I would find, quite by chance, in 2011. Ludicrous!

Yet, as Sherlock Holmes is supposed to have said; ‘When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth’. Well, this was damn impossible and more than improbable, but what other explanation could there be? A cry for help from the seventeenth century, addressed to me, ‘Peter Taylor of Seven Dials’ – personally!

I realised that I had been holding my breath and now inhaled deeply, my mind refusing to believe what my eyes told me, but not knowing what other explanation there could be for this extraordinary book.

THREE

(SUNDAY – EARLY AFTERNOON)

I now had no idea of what to expect when I turned the page. After what I had already read, I was past the stage of being surprised. If it was a forgery, or an elaborate practical joke, then I wanted to find out more. I didn’t want to even speculate if I couldn’t find an explanation – this was just too strange. So, I wasn’t overly surprised when, as I started to read the next page, that it was written in slightly antiquated English, although quite understandable and a usual typeface. I began to suspect that this was indeed a hoax.

But there was something odd about the story, or rather, how the story unfolded. It seemed to me that, as I read, the lines became visible only moments before I got to them – as if some sort of invisible writing was gradually unfolding before my eyes. The strangest thing, however, was the fact that I couldn’t seem to re-read what I had just read; it was as if there was a veil and I couldn’t backtrack – I could only read forwards.

Perhaps I was just tired or still in some state of shock, but it seemed as if I were being pulled along by the narrative, without being able to look back. However, the strangest thing is that I seem to have total recall of the texts, even as I sit here trying to write down the series of events from that week, the texts from the book come back to me, clear as crystal, word for word.

The writing was elegant, beautifully formed letters, with a pleasing flow. I read:

Tom Thatcher, aged about twelve winters. A fair youth, an open, honest face and eyes of purest blue. A pretty nose and perfect lips of coral red, an angelic countenance. His neck is slim, his shoulders too and not rounded. A fair-formed chest and well turned limbs.

He stands about to my chest in height and when he turns his pretty countenance to mine, I can deny him nothing. Little devil in angel’s attire! He knows he has me under his spell and spares no wile or guile whereby to achieve his will! And I allow him to! Mine, then the weakness, but in the face of such delectable beauty and perfect form what can I do but to quietly aquiesce to his every demand, however petty or great. For he has me in such thrall to his beauty and his inventiveness when we are alone that I am in awe of him.

He has kept me entertained many a long night, never seeming to tire and always teasing my old body back to life and vigour ‘tis as if I were a youth myself again! What a cherubic form he has! His boyhood belying his young age, a goodly handspan and of good girth. And his rump! Delightfully dimpled, plump and within its secret place a rosebud of such delectable form – winks at me & invites me in to where I am transported to such shores of pleasure, such a land of lust and wantonness that I can hardly believe my good fortune to have this boy as my private plaything, under my sole command.

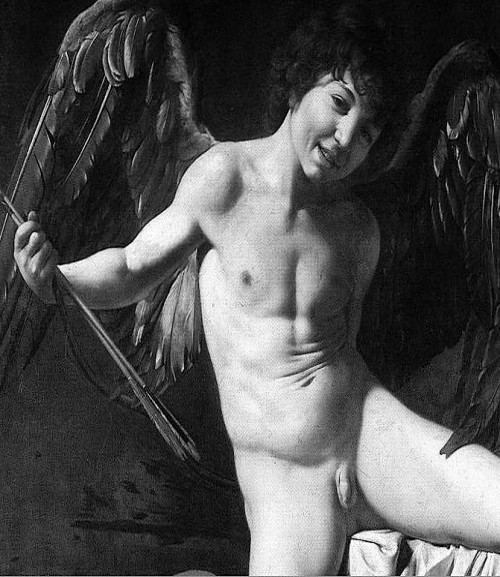

Turning the page, I was faced with a picture:

My Tom is an orphan, left without a mother or father after the Great Sickness two years since. Alas, his sweet younger brother, Percy, also perished before I had the chance to sample the delights his happy form furnished me with. But Tom – my Tom – more than amply makes up for his individual state and his sweet mouth can perform such clever tricks upon my ‘pipe’ – he knows all the sweetest tunes and plays with such dexterity with both hands and lips that I sing, nay shout in the throes of my passion.

I feast upon his tender stalk, his sweet young eggs hardly showing, yet, just recently, he began to bring forth such sweet nectar to rival that of the very gods on Mount Olympus itself!

I feast my eyes upon his body; no blemish – no mark of imperfection to mar his boyish beauty. Not a hair that is not upon his head. His sweet-scented form so patient under my roaming hands! Alas, the time will come when I shall have to give him up; when tempered blade he will have to use upon his cheek and chin. And then around his boyish cocklet, where, daily I inspect him for the first signs of disfiguring sprouting hairs. So far none have appeared, but I am beginning to suspect my little imp/angel of plucking them out.

But for now, my Tom satisfies my every need and anticipates my demands with an obliging meekness which I have taught him to adopt. Long gone are the days I have had to chastise him for any wrongdoing – my beatings now are solely for our mutual pleasure – and when he wields the pincers or the tickling tassels, our heights of rapture are magnified a thousandfold.

Poor boy, when his time comes to leave my service. I shall miss him for a while, perhaps a night or two, but I already have my eye on his successor; a charming little sloe-eyed beauty from the kitchens, barely seven years of age. Alas that I had to dispose of his parents, but with me he shall lack nothing, if he does what he is told. I have him under supervision of the head kitchen lackey, whom I had as a boy this twelve year ago. When I had finished with him, I had him gelded and his tongue cut out to be my caretaker of those precious youths that I need. He knows better than to tamper with my property!

Tom will go the way of the six or seven others I have owned. In a dark , quiet place, late at night. A swift knifestroke to the throat, he will not even know it. A shame, but necessary. I cannot let my goods or chattels fall into the hands of less salubrious characters. Nay, nor can I have my good name besmirched by idle gossip or careless chatter. I shall provide a penny for his winding-sheet. Anonymously, of course.

Ah, here comes my little wanton now, a silken rope around his swanlike neck and his pretty hat with that great feather his only attire, the whip he so craves in his hand, the sweet cocklet already risen. I feel lusty tonight and ready to use him to the full. But first, some wine.

The narrative left me feeling nauseous. The images burned upon my brain. Was the writer that same man in the picture? And the boy in the hat? Tom himself? I had no way of knowing. Poor Tom! Dead by thirteen! Raped and abused for the filthy pleasures of the idle rich. How many more were there? How many poor boys abused and disposed as if they were not even human. Dammit, I bet this man cared more for his dogs than he did for the human lives he so wickedly destroyed.

I found myself weeping. Those poor, innocent boys raped and murdered, mourned by no-one, forgotten by everyone, destined to leave no mark upon this earth.

Despite myself, I turned the page. It seemed as if I was no longer in control of my own actions. I’m sure, that however hard I tried, I would not be able to shut the book until it let me.

Another portrait:

Philip John William Montagu, third Earl of Pevensey,his ‘coming of age’ portrait, aged fourteen.

My son, my only son! My Philip! You have a father’s love, his great love for you, my precious boy! I have watched you as you grew, became a tall, serious youth. You have your mother’s looks, her kind smile, her easy natural grace. The heir to my title and fortune, you shall one day be master here. I adjure you to love, honour and obey the King, as I have done. Love thy brother and when the time comes, you must teach your sons what I must now teach you. You are now fourteen summers and will soon be wed to the fair Catherine. But for now, my darling boy, you are mine; the fruit of my loins. My blood flows in your veins, my seed begot you. Your seed will keep the name of Montagu alive. When your son is your age, you must teach him as I have taught you. For it was out of love for you that I took you to me, my dearest boy. Write it down here, so that you may remember, without fail what passed between us and what you must pass on to your progeny. The love of a father for his son is the most sacred love as was our God in Heaven’s love for his only Son. For this love, have I done these things which you must do. Now, my son, write here what you must recall.

‘My name is Philip Montagu, eldest son of John Montague, the second Earl of Pevensey, Lord of the Marches, Keeper of the Falcon, Knight of the Most Ancient and Honourable Order of the Garter. My father is a great man and has shewn his deep love for me in the only way a man can show his love for his son. I am his, bound to him by blood. I am the fruit of his loins, the keeper of his seed. He hath shewn me the skills I need for a balanced life – how I may best serve him? I kneel before my father, a mighty man and a loving lord. Thus hath he instructed me in the ways of love a father has for his son, a master hath for his servant.

I had just celebrated my fourteenth birthday with great pomp and circumstance, when my lord and master drew me aside.

“Philip, my son,” he said. “Now is the time when boy turns to man and children put away their childish toys. Now you must learn the arts of love.”

He took me to his chamber and after dismissing the servants, bade me approach. My father stands tall and proud, his coal-black hair wild and unruly, bearded and with eyes like steel. His chest is broad his arms and legs thick and strong, like the trunks of mighty oaks.

“Come closer, son” he says in a kindly manner to me as he pours two cups of malmsey for us. He strokes my still beardless cheek, his calloused fingers rough against my smooth skin.

“Drink a cup of wine with me, my pet” he says, “you will feel less nervous and more at ease.”

I must say I am in awe of my father, a giant among men, the lord of all he surveys. His anger can be ferocious and yet I know he can be tender and most loving. I have seen how he is with my mother.

I drink the slightly bitter wine. My father strokes my face, my hair, and before I know it, he has leaned down and placed a loving kiss on my forehead. I feel one of his hands as he strokes my back, and lower. His touch is gentle, yet his eyes seem urgent.

“Come, my boy, a kiss for your father!”

His beard tickles me. I smell the wine on his breath and the other odours of a man.

“My son. Now is the time you must trust your father completely in everything. You must know how I love you, now I need to show you how much I care for you. You and I must share a bond that is unlike all others. It is more scared even than the bond between husband and wife. The love of a son for his father must be complete and unconditional. Can you love me thus?”

“I trust and hope, my lord, that I can” I replied, my mind all awhirl. I knew what was surely to come. My tutor, the monk Ambrosius had been dropping hints for weeks now. Clucking over me like a mother hen, he had shown me the delights of self gratification – he called it the ‘sin of Onan’ but, as he slept in my chamber also, I knew how often brother Ambrosius sinned when he thought I was fast asleep in my bed! Ambrosius had been pleased with my member, calling it a ‘veritable Rod of Aaron’ and when I started to produce seed of my own, he pronounced it ‘sweet as honey’ – I let him teach me the various ways a man can bring pleasure to himself and another. It was Ambrosius who told my father when I was ready for my interview and initiation ito the world of man-love.

“Come, then, my boy, put off thy garb and help me do the same.”

I fumbled with the buttons on my doublet, untied the silk cravat about my neck and untied the strings of my blouse. As I removed my shirt, I saw how my father gazed at me, as if under a spell. His eyes were wide, his mout half-open, his breathing heavy. As my fine lawn shirt fell from my shoulders, he reached over and stroked my chest, making the flesh rise in goosepimples. His touch was light as a feather, almost reverential, as when he took the sacred relics in the chapel to his lips to kiss them.

His hand wandered over my upper body, sending shivers through me. I felt my manhood rising beneath my drawers and pantaloons.

I began to untie the drawstring, loosening my hose. My slippers I kicked off, as my hose fell to the floor. My drawers stood out in front, betraying my state of arousal. I saw my father’s eyes fixed on the outcrop made by my boyflesh and as if he had no control over his actions, his hand gently reached out and caressed my throbbing hardness. His great ham-fist so unlike brother Ambrosius’ feminine hands, I felt the strength of my father in his grasp, so much so that a small cry left my lips. Instantly, my father withdrew his hand, his eyes wide in abject apology. “Forgive me my son, I did not mean to harm you!”

“No harm,” I replied my voice quavering slightly, not through pain, but by the feeling of excitement I felt coursing through my veins. “I did not expect your great strength, that is all!”

By way of reply, or perhaps reparation, my father leant down and kissed me full on the lips, yet so gently, ‘twas like the sigh of a breeze on my mouth. My legs felt as if they would not hold me up any longer. I reached over and held on to my father’s arm, for fear of falling. His hand returned to my staff and gently caressed me through the material of my drawers.

“Come, show your father thy pride and joy!” he whispered into my ear. I untied the bow and eased my undergarment over my stiff, hard tool until I stood before my lord and master – my father – as naked as the day I was born.

The fire burned brightly in the grate, the autumn sun poured through the diamond panes of the window, the tapestries hung on the walls, the silence was like that in a cathedral. I stood before my father as he gazed upon me with what can only be described as wonderment. He knelt before me as if I were a holy statue, his eyes feasting on my naked flesh. Standing there, alone with my father, I suddenly knew what power was. I had this great man, my lord and master, the King’s favourite, on his knees worshipping me – my body – and I knew that I had but to state my wish and it would instantly be granted. I also knew that this was the time to hold my tongue. I would not willingly break the atmosphere of near-holiness which was here. It was as if Time itself had ceased to move forwards, frozen in a moment of eternity.

Then I felt my father’s breath on my throbbing member, then his lips, as they kissed the purple head thrusting out from the skin encasing it, already a few drops on it to show the state of arousal and excitement I was in. I felt my father’s wet, warm tongue, tasting my aching member. Brother Ambrosius had never presumed to perform such an act on me – it would not be right. I had let him lick the seed from my belly after I had pleasured myself, or after he had brought me to climax with his womanly hands, so soft from his potions and prayers.

My father, therefore, was the first to perform this act upon my person and the feeling it produced in me was like a thunderbolt from the blue skies. His mouth, so warm, so wet, engulfed my rod, right down to where the few hairs which grew at its base. I felt my father’s moustaches gently caress my belly, where he suckled on my flesh. I could hardly support myself, my legs shaking like saplings in a gale. I leant towards my father’s kneeling form, resting my weight on him as he sucked my rod. Unable to control myself, I found I was thrusting as far as I could into my father’s mouth, it seemed it went right down his throat. As my moment of expulsion grew near, I called out, to warn my father, so that he could release me, but my cries only made him suck the more, as if he would suck the very life from my body. And then my crisis was upon me and unable to control myself, I cried out as I shot my seed into the warmth of my father’s throat. Five, six times did I eject my seed with such a force, I thought I would faint – I am sure that at the height of my passion I swear I did see the stars and all the heavens exploding in a myriad of colours.

Spent, I fell across my father’s broad shoulders, gasping for air like a trout out of water. My father suckled some more until I could no longer bear the almost painful ecstasy and I withdrew my deflating member from that warm cavern. Not yet trusting myself to stand unaided, I remained leaning over my father’s shoulder, the hairs on his chest tickling my cock. In the throes of my crisis, I must have scratched my father’s back; there were marks made by nails and even a few drops of his blood.

Gently, my father’s hands on my slim waist, he eased me upright and leaning back on his massive haunches, hungrily surveyed my nakedness. I saw specks of white in his black beard – some of my seed had escaped the corner of his mouth.

“Ah, Philip, my angelic boy!” My father seemed not yet to be wholly in this world; his eyes were glazed o’er, his speech almost slurred as though he had drunk too much wine.

“My lovely, beautiful boy!” His massive hand stroked my chest, belly, soft cock and hanging orbs. He reached down between my legs and stroked behind the hanging balls, inching closer and closer to my most secret place, my “hidden treasure” as Ambrosius called it. The monk had hinted that this place was for some men – he did not to say whom, I guessed already by the state of his arousal beneath his cassock – that this secret place, the ‘holy-of-holies’ was the sweetest of all and that when the time came, I should give my father free and willing access to it. “It will hurt,” he warned me, “but after the pain, which shall be shortlived, shall come such pleasure that neither you nor your father will ever forget it.”

The time was approaching, I now knew, for that moment. My dearest wish was that the pain would not make me cry like a girl and that I would be able to please my father, my Lord and Master and also that I would find and enjoy the great delights that brother Ambrosius said I would.

It was a with not a little fear and some trepidation that I gazed down into my father’s ice-blue eyes. He said nothing, only nodded gently as his finger found my deepest, most intimate place and he began to push gently at first with his finger until I felt him push past my barrier. I coulds not help but gasp. There was a brief shot of pain and as the digit moved further, I found myself leaning down upon it. Without any warning, the finger found an obstacle, it seemed right at the root of my member, but within me. It was as if I had been struck by a bolt of lighning and another involuntary cry issued from my lips. My father glanced hastily up with concern, but seeing the smile on my lips, he too smiled and stroked the spot some more. I writhed, pierced upon his finger, unable to speak, unable to think any thoughs save that of feeling pure pleasure. Wave upon wave swept over me and my body glistened under a sheen of sweat. I was amazed to see my cock rise up again, so soon after disgorging its seed. My father slowly withdrew his finger from my very private place and I immediately wanted it back there; I felt empty. My father smiled at my sad face.

“Do not despair, Philip, my beautiful boy! What I shll give you now will far outdo my poor finger’s ministrations!” He rose to his feet, towering over me. “Help me disrobe, boy!” he ordered as he took a large swig of his wine.

For the first time in my life (but not the last) I helped my father divest himself of his garments until he finally stood before me, a giant of a man, the thick black hair matted on his chest, thighs and calves. His powerful chest and flat belly, below which such a monstrous organ – to me at any rate – rose thick and solid, curving towrads his belly. The head of my father’s rod poured forth great quantities of clear fluid, which ran down the throbbing, blue-veined shaft, gathering in the copious amounts of hair about the base and around his vast balls, which hang low – I was reminded of my favourite horse, who, before he mounted a mare, would rear up, his vast cock hard and the balls swinging.

I must have gasped at the sight, for my father, chucking me neath the chin gave a great guffaw as with the other hand he fondled his manhood.

“Tis verily a mighty member!” He laughed again, before his expression became serious again. “Philip, my boy, are you ready for this?”

It dawned on me what my father meant – this was what was awaiting me; my father’s mighty rod, like iron and velvet to the touch, would be put where his finger had just been. I think I must have gone pale, for my father, wiping his great cock across my lips, said to me, “Taste it first, my little plover! Then, you shall have plenty of wine and before you know it, you shall have my joint in your sweet arse and be calling for more!”

Again, he became serious and looked me straight in the eye. “Fear not, my darling boy. It shall not go ill with you. I shall go most carefully. Come! Have some wine and then lie with me upon the bed.”

Hardly being able to tear my eyes away from my father’s great manhood, and as naked as the day I was born, I went to the pitcher and filled my beaker, drinking it down in almost one gulp. Lying on the bed, my father resembled more a Goliath than a man and I wondered how he could possibly let his rod fit my private place. Looking down, I saw that my own boyhood was rampant and leaking great gouts of clear fluid ‘the ladies’ friend’ as Ambrosius called it. He told me that this clear, slightly sticky fluid would help to ease my cock into the dry cunt of any a maid and heighten her pleasure. I only hoped that my father produced enough of it so that I would feel no pain. His member rose from his body, a good two-handspans, glistening in the autumn sunlight, throbbing to his heartbeat. I poured another beaker of wine which I quickly finished off. With slightly unsteady steps, I headed for the bed and my father’s rampant manhood.

“Come, sweet Philip and taste your father’s pride” murmured my father as I crawled on to the bed beside him.

“Lie atop me, boy, with your sweet pole at my face and go down upon me with your fair mouth.”

I climbed on to my father’s great barrel-chest, his coarse hairs rasping aginst my smooth skin. I felt his tongue lick my cock and nuggets as my nose was filled with the almost overpowering aroma of my father’s organ as it throbbed in time to his heartbeat. I was minded of the smell of my hounds when the bitches were in heat.

My lips reached the head of my father’s mighty club ans as I moved in closer. The purple crown, glistening reared to meet my boyish mouth. With some hesitating, I licked upon the musky helmet and, finding that its taste was sweet and much to my liking, I ventured a little further down the mighty rod of my father. My jaw was stretched and I could only manage a thumb’s length of his rampant member before I had a fit of choking and had to relinquish my prize. Meanwhile, my father’s tongue licked my balls, his juices mingling with mine.

“Tis time!” my father murmured. I felt a greasy substance rubbed on to my arse, and one, then two fingers gently probing into my rosebud. The odour was at once familiar and foreign. My father must have sensed my curiosity. He laughed as a third digit stretched my hole.

“Mutton grease with cinnamon” he said as his greased fingers churned in my hole. I shall never forget that sweet yet slightly pungent smell.

“You are ready, my angel,” whispered my father. “Turn around, Philip and straddle me. Lower yourself slowly. Do not worry, I shall hold you so you do not go too fast.” I turned and saw as my father anointed his throbbing pole. I trusted my father with my life, but at that moment, I could not possibly imagine how that great, rampant throbbing piece of manflesh could possibly fit into my arse. My father must have seen my trepidation and, as I was slowly impaled upon that massive organ, he whispered sweet words of encouragement. He held me tightly, as he promised and every time I winced or gave a cry as his massive cock seemed to split me in two, he held me motionless so that I could grow accustomed to him. It seemed to take for ever, being lowered down on to my father’s massive manhood. Luckily my father was as strong as an ox and not once did he let me slip too fast. His cock inched deeper and deeper into me, stretching my hole – it seemed to me – as wide as a grown man’s forearm. How long it seemed to take! However, finally, I felt the coarse hairs of my father on my fundament, and it seemed I could breathe again. “Good boy, my sweet Philip! So tight! So hot!”

My father’s massive manhood was as hard as iron, I felt it surely must come out of my throat!

“Now my lovely boy, ride it, like your favourite pony” said my father, his breathing ragged, his brow beaded as if he had a fever.

I felt his strong hands on my slim hips as he pushed me gently up, then down again, an inch, no more. I felt momentary pain with each thrust, but gradually the pain subsided as another emotion overtook me. My whole world seemed to be centred on my father’s cock and my hole and the sensations I was beginning to feel.

Gradually the discomfort vanished and I ventured longer, deeper strokes, raising myself higher up my father’s shaft and allowing myself to come back down faster. Before I knew it, I was bouncing up and down on his pole with such speed and length of stroke, I knew not where I was. All I wanted was my father’s rod in me, deeper and deeper, longer and longer. My own cocklet rose again, throbbing, harder than it had ever been, juices pouring from its tip and down the shaft, down past my balls, down to where my father’s piston pushed and pulled. My juices lubricated the mighty organ, as it slickly pounded in and out of me. I felt faint, I was seeing stars, when all at once my father pushed me down on to himself and I felt his cock enter deeper than ever and I felt it engorge yet more as my father growled and yelled and shouted, like a crazed person.

All at once, my father went quite still and silent, his arms about me like iron bands. His face was fixed in a rictus of passion, rather like the images of the Holy Catherine in my father’s private chapel, as she felt the living God move within her.

I could hardly breathe, the tears sprang to my ears through a mixture of pain and extreme pleasure, the like of which I had never before experienced. I thought this would be my last moment on this good earth and that within one short breath, I would be face to face with my Maker.

As it was, my ‘maker’ had his body pressed close to mine and then, with a mighty roar, I felt him release his seed deep into my entrails, in great surges like a mighty ocean wave. His eruption triggered another of my own as, untouched, my own organ spewed forth yet again like a mighty fountain, spraying my thick white seed in great ropes, high into the air, to land heavily upon my father’s face, chin, chest and belly. Our shouts mingled; my own piping like a broken reedpipe and my father’s deep, rich and sonorous, like mighty thunder.

All at once, I felt as though the wind had been knocked out of me, and I fell forward, on to my father’s prone, massive chest, the hair matted with sweat and my seed. I felt as his mighty club slowly diminished in size, before pulling out of my fundament with a loud obscene squelch. Unable to control myself, I broke wind and felt a mass of my father’s juices expelled through my hole and down my thighs. Our hearts beat violent tattoos – mine like the skittering of rats in a granary, my father’s like the cannonfire from the battlements.

Slowly, our breathing slowed, the trembling earthquake receded and I lay upon my father’s great naked body, content and fulfilled.

My father called for his manservant. I hurried to cover myself, but my father stopped me. “You will be his lord and master one day, Philip. Remember this! Show no fear, no shame, no cowardice. Be yourself and be proud of who you are and what you represent. Learn this lesson well, my little plover and you shall be a great Lord!”

We lay back on the great bed as the manservant, with two lackeys, washed down our sweatridden, seed-covered bodies with warm cloths and sweet-smelling unguents. We climbed off the massive marriage-bed and my father bade me kneel at his feet. I thought perhaps he wished me to suckle upon his great member again and leant forward as if to take his limply hanging flesh into my mouth, but my father stopped me with a hand under my chin.

“Not now, my sweet boy! Perhaps later. First, You must be marked as a true Montagu! Offer me your breast, boy!”

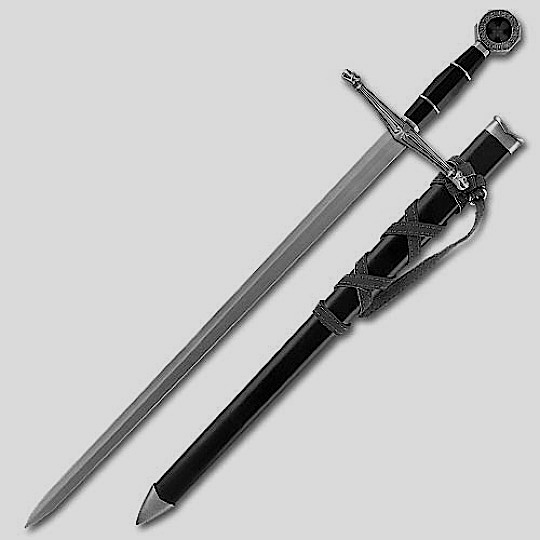

Still naked as the day I was born, I threw back my head and arched my back, kneeling at my father’s feet, so that my breast was offered to him. The two servants came forward and placed a white shirt over my head and a noose of finest silk about my neck. The noose was heavy and one end of it was placed in my hand. There were barbs there and as I clenched it, I felt them pierce my skin and the blood ran down my wrist. Then I saw my father take his great sword from its sheath and, still naked, he placed the point of the razor-sharp blade above my heart on my proffered breast.

“Philip, my son and heir! Be it made known that today thou hast begun the path to manhood and thus doth a father mark his son with this wound of pride, the scar of honour which thou shalt bear unto thy dying day! Let it be known, that I, thy Lord and Master, do endow thee with this mark as a sign to all that thou art to be Master here after my day!”

With that, he pushed the point of his sword into my breast, so that it did truly pierce the skin and my blood did freely flow. I gave a short, sharp cry, not from the pain, for it was a mere scratch, but more from the surprise. My father then knelt before me and suckled at my wound.

“Now I have tasted thy seed and thy blood, Philip my son! We are one!”

He gave a sign to the squires and we were clothed again in rich apparel and my father let the trumpets be sounded and the armaments fired to announce my ‘true’ coming-of-age.

“Let the musicians play sweet songs for my sweet boy!” commanded my father. “Tonight we feast and in three month on Michaelmas shall my Philip be wed.” He turned to me and whispered, his whiskers tickling my ear – “until then, my little plover, we shall have such sweet times together and I shall teach you all I know!”

All this took place three days since and as I write these lines, I am preparing to go to my father’s chamber again – this time I am to plough his furrow. I am most excited.’

* * *

This story left me feeling exhausted. I did not feel as sad as I had after having read the story about poor Tom, but even Philip, despite seeming to have been his father’s willing sexual partner, had still been exploited, this time ostensibly as part of a ‘rite of passage’ but in reality just another underaged boy for his father to abuse. I presumed that, if he survived, and had sons, the young Philip, in his turn would do the same to his offspring – so the cycle continues. Maybe even to this day, I mused, there was a descendant of this Montagu, doing exactly the same as his forbears before him. It seems that sexuality was much freer in times gone past, despite all the talk we have today about sexual freedom.

Power, strength, dominance. Those were what called the shots in earlier ages. A man like Philip’s father would not understand the word – and probably not even the concept of homosexuality. His behaviour was ruled by power and dominance. What we might call ‘feelings’ in these touchy-feely times just didn’t enter into the equation back then. Sex was a tool for domination and subjugation. Men like John Montagu and poor Tom’s tormentor could get away with molesting little boys, because they were lord and master. Through status, money and position, they owned them, like so much furniture or grain. John Montagu might use his son’s coming of age as an excuse, but that’s all it was; an excuse to fuck a little boy and know that there was nothing the lad could do to protect himself. In a way, the boy could be called lucky, if lucky is the right word, for the young aristocrat was in a better position than poor Tom, who, when his pederast tormentor had tired of him, he would be cast aside and murdered in cold blood without a second thought. Philip Montagu kept his life and status – but he also went on to repeat the actions he had undergone on his own sons, if he had any. What goes around, comes around. How true the old adage.

The book had slipped from my hand and I suddenly didn’t have the will, or the urge to pick it up again. As I looked at the small object on the carpet, it appeared to telescope far away into the distance, finally disappearing altogether.

FOUR

(SUNDAY LATE AFTERNOON – EVENING)

I awoke with a start and a severe crick in my neck. It was dark. I looked at my watch; six o’clock. I had slept for almost two hours – an unusually long time. I occasionally snatched a ‘power-nap’ in the afternoon, usually no more than about twenty minutes, which was enough to revitalise me if I was particularly busy.

I eased myself off the sofa, rubbing my sore neck. My sleep had been deep and dreamless, but I wondered why I had awoken with such a start. It was as if I had heard a loud noise and that had woken me. But as I listened to the deep silence around me, I could not recall whether I had in reality heard the sound or just dreamt it.

The traffic outside was light, the shoppers and tourists mostly left the area, a few dropping into the Crown for a drink before going to their homes. Seven Dials was very quiet in the evenings and there were very few people out and about at night around here. I was one of very few residents; most of the houses on my part of the street had long been converted into offices. Ground floors had been turned into either swish specialist shops or businesses, of which Sebastian’s was an example.

On summer nights, one could hear the crowds at Covent Garden, but as winter drew in and the tourists stopped coming in such large numbers, even that faded away. I looked out of my window. I noticed the black van drawing up in front of the house. It was unable to use its usual parking-slot down the side of the house because of the imminent roadworks, so it had to park in front of the building. Without knowing why, I drew back slightly into the darkened room, keeping my eyes on the van. I was curious, yet did not want to be seen to be spying.

Two men got out, a driver and another from the passenger side. They wore duffle-coats and black woolen caps, so it was very hard to see any details or what they might look like. One, I noticed, however, had a very pronounced limp. Both men went round to the back of the van and after a short conversation, the driver disappeared down towards the basement entrance at the side. The other waited by the van. After a short time his partner returned and they opened the double doors at the back of the van and they removed a long bundle, a carpet by the look of it. It seemed very heavy. I watched as they struggled the few steps to the side of the house, before disappearing from view. A few moments later, the driver (the one without a limp) came back and closed and locked the van before disappearing again into the basement of this house, I presumed. I wondered idly if they were smuggling Persian carpets into the country, then admonished myself. “Why on earth do you immediately associate them with criminal activity?” I asked myself out loud. Leaving my own question unanswered, I turned back into the room to turn on some lights.

Even today, months after the event, I am convinced that what I saw was real; although my rational side says it was a trick of the light, the reflection of the streetlights coming into the darkened room. As I said, my rational mind tells me that, but I am convinced that I saw what I saw. I still get a frisson when I recall what happened.

As I turned from looking out of the window, I saw the figure of an extraordinarily beautiful young person standing in the room.

In that short fraction of a second in which I observed the figure, I took in long brown hair, wide brown eyes, pale features, a white lace collar and dark clothes disappearing into the darkness of the room. Whether the figure was a boy or girl, I could not be certain, but I had the distinct impression it was a boy. A boy with exquisitely fine-boned features and such a look of sadness on his face, I felt such a pang of grief that I almost cried out loud. As I said, the image was so clear, so detailed, I was – and still am – convinced that I witnessed an apparition.

Before I could do anything, the vision disappeared. It must have lasted a second or less, but it was so vivid, so real. I will swear to my dying day that it was not a trick of the light and that what I saw was the figure of a young adolescent standing in my room, with a look of such sadness, it tugs at my heart even today.

Without even thinking, I quickly went to my workdesk, where I keep a sketchpad and watercolours ready and did a hasty impression of what I had just seen. As I feverishly worked, my mind recalled more details of the vision I had just seen, such as a gold anchor, or perhaps a cross at the boy’s neck (I am now convinced, in the light of subsequent events that the visitor as I shall call it, was a boy – it could not have been otherwise).

He seemed to have a gentle kindness about him, yet at the same time, there was a certain haughtiness in his manner. But the overbearing feeling I got was that of sadness.

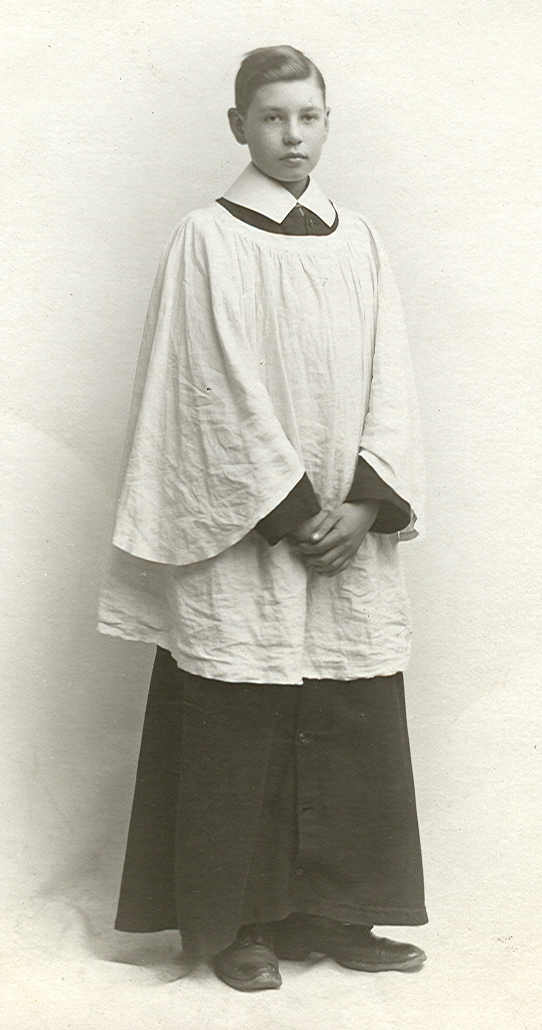

This is what I sketched in haste that dim November evening, immediately after having witnessed him:

I looked at what I had created and am satisfied that the likeness is as accurate as I witnessed it.

As I worked, it seemed as if a name kept repeating itself in my head. James … James… James.

I finished the hasty sketch and all at once, the shock set in and my legs felt very weak. I plomped down on to the nearest chair, wondering how I had managed to have the presence of mind to sketch the boy seconds after having had such an experience – or thinking I had had such an experience.

What a day this was turning out to be! First the strange episode in the imaginary bookshop, then the strange texts in the book I had mysteriously acquired, now a supernatural apparition in my own flat!

I had to call Jeremy, if only to be able to talk to someone else, another human-being, but I knew he would be boarding his flight to the States about now. We had arranged to talk tomorrow. Suddenly, I felt very alone and now, for the first time, more than a little scared. I needed to get out, find other people, if only for the indirect companionship that would offer. I decided to go over the road to the Crown for a drink. Grabbing my paper, I hurried out of the flat, making sure to leave all the lights on. Somehow I didn’t relish the idea of coming home to a darkened home.